How Was "Christabel" Supposed to End?

When the unfinished “Christabel” finally was published in 1816, Coleridge notes in the preface that Part I was written in 1797. However, some scholars believe he mis-remembered the timing, penning the verses instead in the summer of 1798 (Citron 214). Given that the ballad’s conception isn’t clear, it’s no wonder its ending is cloaked in ambiguity.

That summer, 24-year-old and William Wordsworth, 27, fused their lives. For three weeks, Coleridge lived with Wordsworth and his family (Nicolson 8). In early July, they proceeded to Coleridge’s home in Nether Stowey (54). At that point, Coleridge had been married almost two years to Sara Fricker, having met in the midst of a short-lived pantisocracy plotting with Robert Southey in 1794 (Poets.org).

The pantisocracy failed to materialize, but Coleridge created in Nether Stowey a sort of commune with like-minded people: the Wordsworths, who soon moved into a mansion within walking distance; John Cruikshank, the son of the Earl of Egmont’s steward, and his wife, Anna; the curate and his wife, Mrs. Roskilly; a watchmaker, James Cole, and his wife; a vicar of a neighboring hamlet and his daughters; the radical tanner Tom Poole, an outcast among his own family; and Charles Lamb, Coleridge’s beloved boyhood friend from their school days (Nicolson 65).

It was during this “annus mirabilis” (Poetry) when Coleridge likely composed Part I in “four-foot couplets, mostly iambic and anapaestic, used with immense variety, so that the line length varies from seven syllables to ten or eleven” (Oxford). It was to be included in Lyrical Ballads, a collection of poems by Coleridge and Wordsworth to be published in 1798 (Poetry), but because it was unfinished it was removed from the book.

Another plan to publish formulated the following year as part of Robert Southey’s Annual Anthology, to be printed in 1800. However, Coleridge admitted that “[he] had scarce poetic enthusiasm to finish it” (McElderry 442). He then eyed including it in the second edition—more accurately the second volume (Kissane 57)—of Lyrical Ballads. However, on October 6, 1800, Dorothy Wordsworth briefly noted in her journal, “determined not to print Christabel with the L. B.” (McElderry 443). Wordsworth felt “the style was ‘so discordant from my own that it could not be printed along with my poems with any propriety’” (Kissane 58). Coleridge apparently agreed: “‘Christabel’ ‘was in direct opposition to the very purpose for which the Lyrical Ballads were published’” (Poetry).

Before Coleridge composed the second part in the latter half of 1800, he traveled to the Continent with the Wordsworths, studied language and philosophy in Germany, learned of his second son’s death, contributed to the London Morning Post as a political correspondent, lived in England’s remote far north, and, unfortunately, became addicted to opium (Poetry).

Once Part II was written, arrangements to print resurfaced despite the poem still being incomplete. McElderry writes that Coleridge planned to publish the poem on its own rather than in a collection on three separate occasions: in December 1800; on January 6, 1801; and on March 16, 1801. McElderry also included Wordsworth’s statement from April 1801 that it would be printed at the Bulmerian Press (443).

COLERIDGE'S COMPLICATIONS TO COMPLETING "CHRISTABEL"

At least three significant hurdles combined to prevent Coleridge from finishing “Christabel.” One challenge was his well-documented opium addiction. Wordsworth hinted at the instability Coleridge's drug problem created in his comment to Tom Poole in 1809: “‘I give it to you as my deliberate opinion, founded upon proofs which have been strengthening for years, that he neither will nor can execute anything of important benefit to himself, his family, or mankind’” (McElderry 441). Wordsworth would have been an apt appraiser, having by then witnessed a decade of Coleridge’s behavioral patterns. Coleridge himself indirectly referenced that issue in August 1816, when he “confidently [said] ... that at last he was in the state of mind and health ‘to finish my Christabel” (Holmes 438).

In explaining the second challenge in July 1833, Coleridge again alluded to the first: “‘I could write as good verses now as ever I did, if I were perfectly free from vexations . . . The reason of my not finishing Christabel is not that I don’t know how to do it—for I have, as I always had, the whole plan entire from beginning to end in my mind; but I fear I could not carry on with equal success the execution of the idea, and extremely subtle and difficult one’” (McElderry 443-4). In short, he feared he couldn't live up to the extraordinary standard he established.

Alois Brandl, in Samuel Taylor Coleridge and the English Romantic School, agreed with the issue of maintaining such high quality: “‘Pantisocracy,’ ‘Kubla Khan,’ and Christabel—his most brilliant undertakings,—remained mere fragments; and, strange to say, we are glad they did so remain” (214).

As for the third challenge, Coleridge blamed his laziness in the preface in 1816.

E. H. Coleridge explains that Coleridge wrote the following preface for the 1816 edition, and it remained unchanged for the 1828 and 1829 editions. Two sentences, however, were removed from the 1834 edition, which was published after his death on July 25 of that year: the third sentence, which offers an explanation about why the poem is unfinished; and the fourth, which conveys confidence that Coleridge will complete the poem within the calendar year (213-5). These are italicized below.

Preface

The first part of the following poem was written in the year 1797, at Stowey, in the county of Somerset. The second part after my return from Germany, in the year 1800, at Keswick, Cumberland. Since the latter date, my poetic powers have been, till very lately, in a state of suspended animation. But as, in my very first conception of the tale, I had the whole present to my mind, with the wholeness, no less than the liveliness of a vision; I trust that I shall be able to embody in verse the three parts yet to come, in the course of the present year [omitted in 1834 ed., (EHC 213).] It is probable that if the poem had been finished at either of the former periods, or if even the first and second part had been published in the year 1800, the impression of its originality would have been much greater than I dare at present expect. But for this, I have only my own indolence to blame. The dates are mentioned for the exclusive purpose of precluding charges of plagiarism or servile imitation from myself. For there is amongst us a set of critics, who seem to hold, that every possible thought and image is traditional; who have no notion that there are such things as fountains in the world, small as well as great and who would therefore charitably derive every rill they behold flowing, from a perforation made in some other man's tank. I am confident however, that as far as the present poem is concerned, the celebrated poets [Sir Walter Scott and Lord Byron (EHC 215)] whose writings I might be suspected of having imitated, either in particular passages, or in the tone and the spirit of the whole, would be among the first to vindicate me from the charge, and who, on any striking coincidence, would permit me to address them in this doggerel [ed. 1816, 1828, 1829 (ECH 215)] version of two monkish Latin hexameters [Coleridge translated the following lines in November 1801 (EHC 215)].

Yes mine and it is likewise yours;

But an if this will not do;

Let it be mine, good friend for I

Am the poorer of the two.

I have only to add, that the metre of the Christabel is not, properly speaking, irregular, though it may seem so from its being founded on a new principle: namely, that of counting in each line the accents, not the syllables. Though the latter may vary from seven to twelve, yet in each line the accents will be found to be only four. Nevertheless this occasional variation in number of syllables is not introduced wantonly, or for the mere ends of convenience, but in correspondence with some transition, in the nature of the imagery or passion.

ENDINGS IMAGINED

The idea of Coleridge finishing the ballad is recorded on several other occasions, including that it was his “continuing dream,” in April 1807 (Holmes 94); because of his “buoyant” mood in, November 1807 (113); because of the rejection of a close female companion, in 1810 (208); an idea to “extend it and give new characters, and a greater number of incidents,” in 1820 (Allsop 94); and, on his 51st birthday in 1832, if he were "free to do so, [he] could compose the third part of Christabel . . . ” (Holmes 538).

If an ending was in fact planned, what would it have been?

James Dykes Campbell wrote in The Poetical Works of Samuel Taylor Coleridge that the planned ending “involves principally the disappearance of Geraldine in the character of the daughter of Lord Roland de Vaux, her re-appearance in the guise of the absent lover of Christabel, and the foiling of her evil influence by the return of her true lover” (McElderry 437).

Coleridge’s son Derwent, in The Poems of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, explained that “[t]he sufferings of Christabel were to have been represented as vicarious, endured for ‘her lover far away’” (52).

At least two scholars who had never met Coleridge attempted to answer that question in the first half of the 20th century.

George Stanislaus Connell

In 1916, one hundred years after the first publication of “Christabel,” George Stanislaus Connell composed his take on the ending in the three expected parts. In the introduction to the project, he writes that the “verses here offered as third, fourth and fifth parts of Coleridge's Christabel were printed in 1916, during my sojourn in Fribourg, Switzerland, but owing to the prolongation of the War that edition was not published.”

George Stanislaus Connell’s ending of “Christabel”

B. R. McElderry, Jr.

Twenty years later, in 1936, B. R. McElderry, Jr., published an article in the scholarly journal Studies in Philology titled “Coleridge’s Plan for Completing ‘Christabel.’” He first argues that Coleridge did, indeed, have at a sense of what was to come in the final three parts (437-45). He then offers a summary of Parts I and II (446-7) before hypothesizing about what Coleridge had in mind for the ending, based on the story that Gillman puts forth in his biography, The Life of Samuel Taylor Coleridge (447).

Summary of Parts I and II

"At midnight Christabel steals from the castle of her father, Sir Leoline; she goes to the wood nearby, and in front of an old oak tree she kneels to pray for her absent lover. Startled by a moan, she discovers on the other side of the tree a strange lady, Geraldine. The stranger tells of being abducted by five unknown warriors; they have placed her beneath the oak, swearing to return soon. Geraldine has heard the castle bell, and asks for shelter. The two enter the castle, and go up to Christabel's room. There Christabel confides that her mother died at her birth, promising to hear the castle bell on her daughter's wedding day. Geraldine, in an altered voice, warns off the spirit of Christabel's mother; promises to repay Christabel's kindness; prays; lies down beside Christabel and tells her that she is under a strange spell. The Conclusion to Part I describes Christabel's troubled sleep.

Part II. Next morning on the tolling of the bell, Geraldine wakes Christabel, who takes her guest to her father, Sir Leoline. He is much moved to discover that Geraldine is the daughter of an old friend, Lord Roland de Vaux of Tryermaine, with whom Sir Leoline had quarreled years before. He decides that he will atone for the quarrel and renew the friendship by protecting Geraldine and punishing her persecutors. At this moment a vision falls on Christabel, and she shrinks from Geraldine, asking that the visitor be sent away. But Sir Leoline orders the bard Bracy to seek out Lord Roland, inform him of Geraldine's safety, and invite him to come for her. Because of a strange dream about a dove endangered by a serpent, Bracy objects to undertaking a journey on this day. Sir Leoline is unimpressed, and re-assures Geraldine. Again seized by a vision-this time Geraldine's eyes appear as those of a serpent- Christabel is terrified, and once more begs her father to send Geraldine away. Chagrined and angered at his daughter's discourtesy, Sir Leoline orders Bracy to set off without delay. The lyric Conclusion of Part II, whatever its precise significance, adds nothing to the narrative."

Summary of the ending based on the story given by Gillman

"Over the mountains, the Bard, as directed by Sir Leoline, "hastes " with his disciple; but in consequence of one of those inundations supposed to be common to this country, the spot only where the castle once stood is discovered, the edifice itself being washed away. He determines to return. Geraldine being acquainted with all that is passing, like the Weird Sisters in Macbeth, vanishes. Re-appearing, however, she waits the return of the Bard, exciting in the mean time by her wily arts, all the anger she could rouse in the Baron's breast, as well as that jealousy of which he is described to have been susceptible. The old Bard and the youth at length arrive, and therefore she can no longer personate the character of Geraldine, the daughter of Lord Roland de Vaux, but changes her appearance to that of the accepted though absent lover of Christabel. Next ensues a courtship most distressing to Christabel, who feels-she knows not why- great disgust for her once favoured knight. This coldness is very painful to the Baron, who has no more conception than herself of the supernatural transformation. She at last yields to her father's entreaties, and consents to approach the altar with this hated suitor. The real lover returning, enters at this moment, and produces the ring which she had once given him in sign of her betrothment. Thus defeated, the supernatural being Geraldine disappears. As predicted, the castle bell tolls, the mother's voice is heard, and to the exceeding great joy of the parties, the rightful marriage takes place, after which follows a reconciliation and explanation between the father and daughter."

That summer, 24-year-old and William Wordsworth, 27, fused their lives. For three weeks, Coleridge lived with Wordsworth and his family (Nicolson 8). In early July, they proceeded to Coleridge’s home in Nether Stowey (54). At that point, Coleridge had been married almost two years to Sara Fricker, having met in the midst of a short-lived pantisocracy plotting with Robert Southey in 1794 (Poets.org).

The pantisocracy failed to materialize, but Coleridge created in Nether Stowey a sort of commune with like-minded people: the Wordsworths, who soon moved into a mansion within walking distance; John Cruikshank, the son of the Earl of Egmont’s steward, and his wife, Anna; the curate and his wife, Mrs. Roskilly; a watchmaker, James Cole, and his wife; a vicar of a neighboring hamlet and his daughters; the radical tanner Tom Poole, an outcast among his own family; and Charles Lamb, Coleridge’s beloved boyhood friend from their school days (Nicolson 65).

It was during this “annus mirabilis” (Poetry) when Coleridge likely composed Part I in “four-foot couplets, mostly iambic and anapaestic, used with immense variety, so that the line length varies from seven syllables to ten or eleven” (Oxford). It was to be included in Lyrical Ballads, a collection of poems by Coleridge and Wordsworth to be published in 1798 (Poetry), but because it was unfinished it was removed from the book.

Another plan to publish formulated the following year as part of Robert Southey’s Annual Anthology, to be printed in 1800. However, Coleridge admitted that “[he] had scarce poetic enthusiasm to finish it” (McElderry 442). He then eyed including it in the second edition—more accurately the second volume (Kissane 57)—of Lyrical Ballads. However, on October 6, 1800, Dorothy Wordsworth briefly noted in her journal, “determined not to print Christabel with the L. B.” (McElderry 443). Wordsworth felt “the style was ‘so discordant from my own that it could not be printed along with my poems with any propriety’” (Kissane 58). Coleridge apparently agreed: “‘Christabel’ ‘was in direct opposition to the very purpose for which the Lyrical Ballads were published’” (Poetry).

Before Coleridge composed the second part in the latter half of 1800, he traveled to the Continent with the Wordsworths, studied language and philosophy in Germany, learned of his second son’s death, contributed to the London Morning Post as a political correspondent, lived in England’s remote far north, and, unfortunately, became addicted to opium (Poetry).

Once Part II was written, arrangements to print resurfaced despite the poem still being incomplete. McElderry writes that Coleridge planned to publish the poem on its own rather than in a collection on three separate occasions: in December 1800; on January 6, 1801; and on March 16, 1801. McElderry also included Wordsworth’s statement from April 1801 that it would be printed at the Bulmerian Press (443).

COLERIDGE'S COMPLICATIONS TO COMPLETING "CHRISTABEL"

At least three significant hurdles combined to prevent Coleridge from finishing “Christabel.” One challenge was his well-documented opium addiction. Wordsworth hinted at the instability Coleridge's drug problem created in his comment to Tom Poole in 1809: “‘I give it to you as my deliberate opinion, founded upon proofs which have been strengthening for years, that he neither will nor can execute anything of important benefit to himself, his family, or mankind’” (McElderry 441). Wordsworth would have been an apt appraiser, having by then witnessed a decade of Coleridge’s behavioral patterns. Coleridge himself indirectly referenced that issue in August 1816, when he “confidently [said] ... that at last he was in the state of mind and health ‘to finish my Christabel” (Holmes 438).

In explaining the second challenge in July 1833, Coleridge again alluded to the first: “‘I could write as good verses now as ever I did, if I were perfectly free from vexations . . . The reason of my not finishing Christabel is not that I don’t know how to do it—for I have, as I always had, the whole plan entire from beginning to end in my mind; but I fear I could not carry on with equal success the execution of the idea, and extremely subtle and difficult one’” (McElderry 443-4). In short, he feared he couldn't live up to the extraordinary standard he established.

Alois Brandl, in Samuel Taylor Coleridge and the English Romantic School, agreed with the issue of maintaining such high quality: “‘Pantisocracy,’ ‘Kubla Khan,’ and Christabel—his most brilliant undertakings,—remained mere fragments; and, strange to say, we are glad they did so remain” (214).

As for the third challenge, Coleridge blamed his laziness in the preface in 1816.

E. H. Coleridge explains that Coleridge wrote the following preface for the 1816 edition, and it remained unchanged for the 1828 and 1829 editions. Two sentences, however, were removed from the 1834 edition, which was published after his death on July 25 of that year: the third sentence, which offers an explanation about why the poem is unfinished; and the fourth, which conveys confidence that Coleridge will complete the poem within the calendar year (213-5). These are italicized below.

Preface

The first part of the following poem was written in the year 1797, at Stowey, in the county of Somerset. The second part after my return from Germany, in the year 1800, at Keswick, Cumberland. Since the latter date, my poetic powers have been, till very lately, in a state of suspended animation. But as, in my very first conception of the tale, I had the whole present to my mind, with the wholeness, no less than the liveliness of a vision; I trust that I shall be able to embody in verse the three parts yet to come, in the course of the present year [omitted in 1834 ed., (EHC 213).] It is probable that if the poem had been finished at either of the former periods, or if even the first and second part had been published in the year 1800, the impression of its originality would have been much greater than I dare at present expect. But for this, I have only my own indolence to blame. The dates are mentioned for the exclusive purpose of precluding charges of plagiarism or servile imitation from myself. For there is amongst us a set of critics, who seem to hold, that every possible thought and image is traditional; who have no notion that there are such things as fountains in the world, small as well as great and who would therefore charitably derive every rill they behold flowing, from a perforation made in some other man's tank. I am confident however, that as far as the present poem is concerned, the celebrated poets [Sir Walter Scott and Lord Byron (EHC 215)] whose writings I might be suspected of having imitated, either in particular passages, or in the tone and the spirit of the whole, would be among the first to vindicate me from the charge, and who, on any striking coincidence, would permit me to address them in this doggerel [ed. 1816, 1828, 1829 (ECH 215)] version of two monkish Latin hexameters [Coleridge translated the following lines in November 1801 (EHC 215)].

Yes mine and it is likewise yours;

But an if this will not do;

Let it be mine, good friend for I

Am the poorer of the two.

I have only to add, that the metre of the Christabel is not, properly speaking, irregular, though it may seem so from its being founded on a new principle: namely, that of counting in each line the accents, not the syllables. Though the latter may vary from seven to twelve, yet in each line the accents will be found to be only four. Nevertheless this occasional variation in number of syllables is not introduced wantonly, or for the mere ends of convenience, but in correspondence with some transition, in the nature of the imagery or passion.

ENDINGS IMAGINED

The idea of Coleridge finishing the ballad is recorded on several other occasions, including that it was his “continuing dream,” in April 1807 (Holmes 94); because of his “buoyant” mood in, November 1807 (113); because of the rejection of a close female companion, in 1810 (208); an idea to “extend it and give new characters, and a greater number of incidents,” in 1820 (Allsop 94); and, on his 51st birthday in 1832, if he were "free to do so, [he] could compose the third part of Christabel . . . ” (Holmes 538).

If an ending was in fact planned, what would it have been?

James Dykes Campbell wrote in The Poetical Works of Samuel Taylor Coleridge that the planned ending “involves principally the disappearance of Geraldine in the character of the daughter of Lord Roland de Vaux, her re-appearance in the guise of the absent lover of Christabel, and the foiling of her evil influence by the return of her true lover” (McElderry 437).

Coleridge’s son Derwent, in The Poems of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, explained that “[t]he sufferings of Christabel were to have been represented as vicarious, endured for ‘her lover far away’” (52).

At least two scholars who had never met Coleridge attempted to answer that question in the first half of the 20th century.

George Stanislaus Connell

In 1916, one hundred years after the first publication of “Christabel,” George Stanislaus Connell composed his take on the ending in the three expected parts. In the introduction to the project, he writes that the “verses here offered as third, fourth and fifth parts of Coleridge's Christabel were printed in 1916, during my sojourn in Fribourg, Switzerland, but owing to the prolongation of the War that edition was not published.”

George Stanislaus Connell’s ending of “Christabel”

B. R. McElderry, Jr.

Twenty years later, in 1936, B. R. McElderry, Jr., published an article in the scholarly journal Studies in Philology titled “Coleridge’s Plan for Completing ‘Christabel.’” He first argues that Coleridge did, indeed, have at a sense of what was to come in the final three parts (437-45). He then offers a summary of Parts I and II (446-7) before hypothesizing about what Coleridge had in mind for the ending, based on the story that Gillman puts forth in his biography, The Life of Samuel Taylor Coleridge (447).

Summary of Parts I and II

"At midnight Christabel steals from the castle of her father, Sir Leoline; she goes to the wood nearby, and in front of an old oak tree she kneels to pray for her absent lover. Startled by a moan, she discovers on the other side of the tree a strange lady, Geraldine. The stranger tells of being abducted by five unknown warriors; they have placed her beneath the oak, swearing to return soon. Geraldine has heard the castle bell, and asks for shelter. The two enter the castle, and go up to Christabel's room. There Christabel confides that her mother died at her birth, promising to hear the castle bell on her daughter's wedding day. Geraldine, in an altered voice, warns off the spirit of Christabel's mother; promises to repay Christabel's kindness; prays; lies down beside Christabel and tells her that she is under a strange spell. The Conclusion to Part I describes Christabel's troubled sleep.

Part II. Next morning on the tolling of the bell, Geraldine wakes Christabel, who takes her guest to her father, Sir Leoline. He is much moved to discover that Geraldine is the daughter of an old friend, Lord Roland de Vaux of Tryermaine, with whom Sir Leoline had quarreled years before. He decides that he will atone for the quarrel and renew the friendship by protecting Geraldine and punishing her persecutors. At this moment a vision falls on Christabel, and she shrinks from Geraldine, asking that the visitor be sent away. But Sir Leoline orders the bard Bracy to seek out Lord Roland, inform him of Geraldine's safety, and invite him to come for her. Because of a strange dream about a dove endangered by a serpent, Bracy objects to undertaking a journey on this day. Sir Leoline is unimpressed, and re-assures Geraldine. Again seized by a vision-this time Geraldine's eyes appear as those of a serpent- Christabel is terrified, and once more begs her father to send Geraldine away. Chagrined and angered at his daughter's discourtesy, Sir Leoline orders Bracy to set off without delay. The lyric Conclusion of Part II, whatever its precise significance, adds nothing to the narrative."

Summary of the ending based on the story given by Gillman

"Over the mountains, the Bard, as directed by Sir Leoline, "hastes " with his disciple; but in consequence of one of those inundations supposed to be common to this country, the spot only where the castle once stood is discovered, the edifice itself being washed away. He determines to return. Geraldine being acquainted with all that is passing, like the Weird Sisters in Macbeth, vanishes. Re-appearing, however, she waits the return of the Bard, exciting in the mean time by her wily arts, all the anger she could rouse in the Baron's breast, as well as that jealousy of which he is described to have been susceptible. The old Bard and the youth at length arrive, and therefore she can no longer personate the character of Geraldine, the daughter of Lord Roland de Vaux, but changes her appearance to that of the accepted though absent lover of Christabel. Next ensues a courtship most distressing to Christabel, who feels-she knows not why- great disgust for her once favoured knight. This coldness is very painful to the Baron, who has no more conception than herself of the supernatural transformation. She at last yields to her father's entreaties, and consents to approach the altar with this hated suitor. The real lover returning, enters at this moment, and produces the ring which she had once given him in sign of her betrothment. Thus defeated, the supernatural being Geraldine disappears. As predicted, the castle bell tolls, the mother's voice is heard, and to the exceeding great joy of the parties, the rightful marriage takes place, after which follows a reconciliation and explanation between the father and daughter."

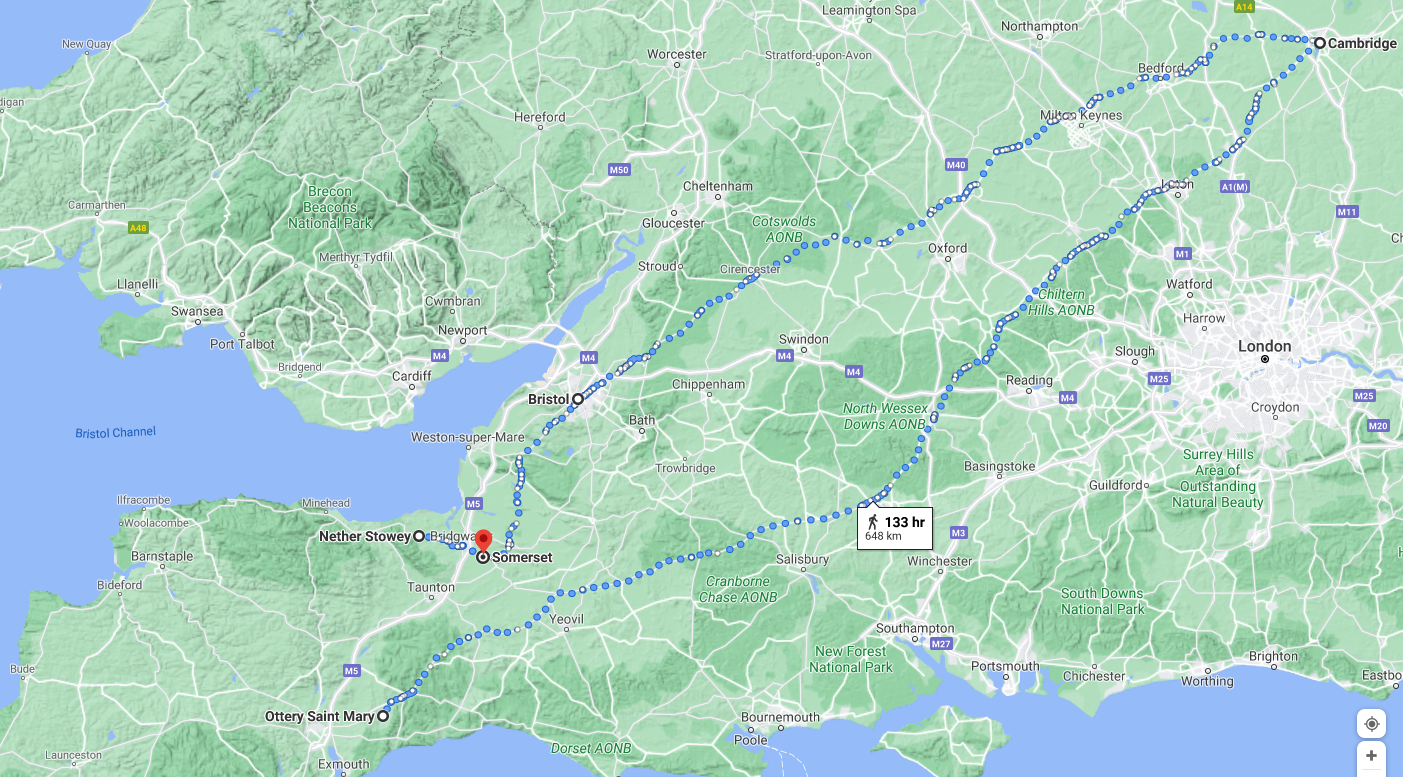

Map 1.

Coleridge moved around. A lot. This map shows his dwelling places from the time he was born until he and the Wordsworths traveled to the Continent.

Born in Ottery St. Mary (southwest).

Attended Christ's Hospital, a charity school for boys in London (east-central).

Attended Jesus College as a sizar (financially aided) at the University of Cambridge (northeast).

Lectured in Bristol (central).

Moved to Clevedon after marriage to Sara.

Preached occasionally in Tauton (southwest) and Bath (central).

Moved with wife and son to Nether Stowey (southwest).

Coleridge moved around. A lot. This map shows his dwelling places from the time he was born until he and the Wordsworths traveled to the Continent.

Born in Ottery St. Mary (southwest).

Attended Christ's Hospital, a charity school for boys in London (east-central).

Attended Jesus College as a sizar (financially aided) at the University of Cambridge (northeast).

Lectured in Bristol (central).

Moved to Clevedon after marriage to Sara.

Preached occasionally in Tauton (southwest) and Bath (central).

Moved with wife and son to Nether Stowey (southwest).

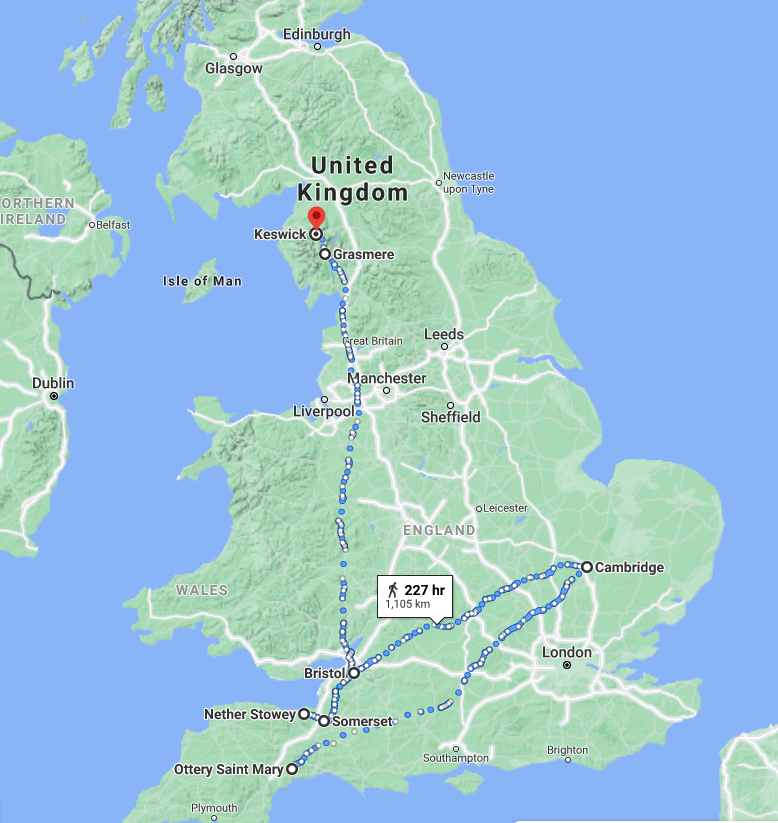

Map 2.

After returning from the Continent in 1800, Coleridge settled with his family in Keswick (remote far north) while the Wordsworths lived nearby in Grasmere. It was there he wrote Part II of "Christabel" in the latter half of 1800. In 1804, he began a two-year stint working as a government official on the island of Malta in Greece. Upon his return in 1806, he separated from his wife and lived most of the rest of his life in London. The exception was an especially nomadic two years staying with friends and family as he suffered from his opium and alcohol addiction.

After returning from the Continent in 1800, Coleridge settled with his family in Keswick (remote far north) while the Wordsworths lived nearby in Grasmere. It was there he wrote Part II of "Christabel" in the latter half of 1800. In 1804, he began a two-year stint working as a government official on the island of Malta in Greece. Upon his return in 1806, he separated from his wife and lived most of the rest of his life in London. The exception was an especially nomadic two years staying with friends and family as he suffered from his opium and alcohol addiction.